Healing Spaces Reflect Indigenous Values at Toronto Shelter for Women and Children

Key Highlights

- The shelter’s design incorporates natural elements like water, earth, and sky to symbolize healing and nourishment, reflecting Indigenous principles.

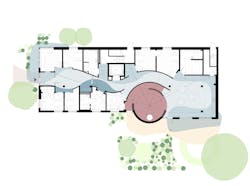

- Fluid architectural features such as curved ceilings, circular ceremonial spaces, and stream-like exterior canopies evoke water flow and interconnectedness, supporting a sense of continuity.

- The floorplan provides a variety of communal and private spaces, including shared kitchens, quiet rooms, and interconnected bedrooms, promoting agency and comfort for residents.

A haven for Indigenous women and children escaping violence, Anduhyaun Emergency Shelter reflects cultural values that support women and their children. As Toronto’s only transitional Indigenous Violence Against Women shelter, LGA Architectural Partners designed Anduhyaun Emergency Shelter in close collaboration with Indigenous elders.

Indigenous Worldview Shapes the Foundation

Brock James, architect and partner at LGA Architectural Partners, described the influence of nature in the design of the 3-story, 18-room shelter. Nods to the natural elements of water, earth, and sky, which are related to healing and nourishment, can be seen throughout. The design concept was influenced by Anduhyaun’s former executive director, Blanche Meawassige.

“When we were doing bubble layouts, [Meawassige] would say, ‘It looked very rectilinear. I’m not seeing an Indigenous world view.’ She would talk about the idea of continuity, of interconnectedness,” James said. “Those things are very inspirational and immediately, to a designer, start to speak to geometry and form.”

Meawassige also spoke about a sage rooted in the mud that raised toward the sun, even when supple in the wind, as a symbol of strength. She wanted the building to feel alive and support growth through an interconnection to the natural world.

Architecture Rooted in Nature

LGA Architectural Partners utilized water as a metaphor, making a thoughtful departure from the traditional angularity of conventional construction. Incorporation of fluidity appears in bulkhead ceiling lines within the various rooms, hallways, and a circular design for the ceremonial space. The building’s exterior entrance canopy begins a stream-like flow through the shelter and to the sanctity of the back garden. As clients enter through the vestibule, they pass by rooms for intake, counseling, the Elders, and staff.

“The ceilings are important within this space,” James said. “The bulkheads participate in the space by peeling off the walls. They create compression in quite a natural feeling space, almost like a space carved by the flow of water.”

To avoid disruption in the flow of the hallways, the doors are subtly folded into recessed entries behind the curving walls. This creates a gentle threshold between the hallway and the room compared to a traditional corridor, while also supporting continuity and bringing in borrowed light from the exterior windows through the glass doors.

Clients will also see luminous blue glazed tiles that reflect the sunlight, like the water’s surface, throughout the hallway. LGA Architectural Partners was mindful about maximizing the non-profit’s invested money through thoughtful material selections and installation.

“One of the things we always want to do in our non-profit work is to have the idea of carefulness or care in the space—meaning things are done well, considered, and thoughtful,” James explained. “We take a lot of care in the detailing of this tile. We worked closely with the contractor on this tile so that things are executed well.”

The Ceremonial Heart

As the blue-glazed tile walls give way to natural cedar cladding, clients reach the Nookomis Dibik-Giizis, which means Grandmother Moon in Ojibwe. This ceremonial space is a deeply evocative circular room that serves as the heart of the community. With various cedar shapes available, James described how the team created numerous patterns during the pandemic before settling on the subtle descending pattern evocative of waves.

“We would cut out miniatures of all the potential shapes and have a bunch of patterns to try,” James said. “Certain ones started to emerge. We liked this one because it has flow to it and it’s a subtle descending pattern that, on a subjective level, seemed to work with the water.”

The cedar cladding was installed from the floor to the ceiling to achieve the desired layering.

The first floor’s engineered wood flooring is arranged in a radial pattern and converges at the center of the Nookomis, a 20-foot room. One spotlight was installed as a representation of the sun and moon. A deep sumac red paint was used on the walls, along with a red foam near the ceiling to balance the acoustics. The Nookomis supports sacred smudging ceremonies with hidden ventilation to clear the smoke when needed.

“We wanted the space to be embracing. It’s a heavy color, so it holds you in, and it’s in contrast to the other colors. I find that with these dark colors, although it is an embracing kind of space, in the darkness it expands a little bit,” James said. “The definition where the wall meets the ceiling is ambiguous, and in that way, it paradoxically expands. Trying to evoke the Earth, the cardinal directions, and the movement of the sun gets at an idea of a space that is hard to define, which felt good.”

The flexible space features a curved, track pocket door allowing the ceremonial space to open into the kitchen or to close and serve as a refuge for clients and staff to recharge, as well as a place of worship, meditation, meetings, and other gatherings. The room’s circular design references renewal, spirituality, and the circle of life.

Safe and Communal Spaces

A shared kitchen and dining area with expansive windows looking out into a private, outdoor garden serves as a shared space where residents cook with autonomy or together as they mingle with the shelter community.

Outside clients can enjoy a garden and fire pit for ceremonies with the privacy of a fenced yard.

“It allows the ground floor to be more porous because of the protection of the fence,” James said.

Additional security features on the premises include a two-stage entry with sightlines for staff to the video buzzer, window blinds, and one point of entry to and from the building.

The second and third residential floors have bedroom suites, communal areas, quiet rooms, and children’s play areas. The bedroom floor plans include three-piece bathrooms, a wardrobe, an operable window, and adjustable lighting on the wall over the bed and desk. A unique design feature is the curved connection between the wall and ceiling, reinforcing the gentleness and natural flow of water. Some rooms are interconnected to support women with children, who need a place to stay.

“Here’s a lounge on your floor with a nice window, comfortable seating, and you can do your laundry,” he said. “This is the idea in shelter design—you purposely give a variety of places for people to participate, from private to more shared and more public in the community, and you give them agency and control over how they want to occupy the space.”

Sightlines and color were important design elements on the residential floors to promote wayfinding and ground those floors to the Earth. The second-floor colors were inspired by water with pastel blues. The third-floor colors were inspired by the sky at sunrise and sunset, shifting from mauve to yellow.

LGA Architectural Partners designed the Anduhyaun Emergency Shelter to support Indigenous women and children escaping domestic violence. Through a purposeful design rooted in Indigenous values, the shelter’s revitalization and transformative spaces help women and children feel supported and empowered on their healing journeys.

About the Author

Lauren Brant

Staff Writer, interiors+sources and BUILDINGS

Lauren Brant is Staff Writer for both interiors+sources and BUILDINGS. She is an award-winning editor and reporter whose work has appeared in daily and weekly newspapers. In 2020, the weekly newspaper won the Rhoades Family Weekly Print Sweepstakes—the division winner across the state's weekly newspapers. Lauren was also awarded the top feature photo across Class A papers. She holds a B.A. in journalism and media communications from Colorado State University-Fort Collins and a M.S. in organizational management from Chadron State College.