Cultivating Community at Chicago’s Oakland Museum & Garden

A corner pocket park firmly rooted in history and community pride in Chicago’s densely urban South Side, the Oakland Museum & Garden is an outdoor respite where the art and natural setting embodies cultural heritage. Adjacent to the Lake Michigan shoreline, current green trail systems, and well-publicized future Bronzeville Trail, the evolving sculpture garden is admired by visitors who arrive by foot, bike, and vehicle. The formerly vacant city lot at the Southwest corner of east 41st Place and south Lake Park Avenue wasn’t always so inviting.

A Garden Rooted in Cultural Identity

The Oakland Museum & Garden grew out of a single person’s artistic vision to transform one of several neglected Chicago lots into a prideful place of care and beauty. For more than two decades, the late self-taught sculptor, teacher, and Oakland community resident Milton Mizenburg, Jr. created expressive wood sculptures on the site. With a larger-than-life personality, this is where Mizenburg nurtured his outdoor gallery, uplifting his community friends, neighbors, and visitors passing through. The founder and recognized Chicago artist was passionate about creating positive change and personal wellbeing through actionable artmaking, teaching, and impromptu dialogue in a public and natural setting. He generously donated many artworks to enrich the community.

For five years, I watched my neighbor and friend as he hand-chiseled, shaped, and painted his expressive wood sculptures. With a few neighbors, we began clearing up and creating garden spaces to enhance the surrounding environment prior to Mizenburg’s passing in 2016. I recognized that what he was doing had immense public value, and began organizing the site as a viable space to honor Mizenburg’s legacy and safeguard the vacant property from an uncertain future.

One of our neighbors and the sculptor’s mentee, composer, educator, and live PA performer, Lional “Brother-El” Freeman commented from decades ago, “I was one of the young people who helped clean up the decay of drug needles, cars, tires, couches, and dirty mattress. Mr. Mizenburg gave me an understanding of what it means to transform space before it was popular.”

New Project Type with Familiar Challenges

During the early stages of becoming a sustaining community cultural space, the existing wedge of land was edging into a decaying side ground. Socially, the open space was sporadically used as an informal area for spontaneous gatherings. Our small, shared asset lay somewhere between the realms of disuse and tended ownership, an ambiguous state common to vacant properties without coordinated stewardship. Receiving a micro-grant before the pandemic helped us send a message that the lot was not abandoned.

Preservation and long-term sustainability would need to happen on several fronts: First, formally protecting the land from commercial development was paramount to preserve the property as a community open space. We also recognized that the founder’s contributions to the community deserved special legacy commemoration. And generally, the physical space could be better organized and more user friendly for our multi-generational community. While the scope of work hadn’t completely taken shape, it would be quite an undertaking, and we needed allies. The Mizenburg family and late community leader and alderperson Shirley J. Newsome valued the idea to protect the heritage site, providing grassroots support.

Public design was familiar, but the site acquisition and project sustainability were interdependent on a host of complexities. We were ill prepared for a process with layers of challenges including non-dedicated property ownership and inconsistent neighbor participation. We had to coordinate progress with a rotation of elected government officials, learning how to fund essential project needs and to keep momentum with volunteers. Things got unexpectedly messy while discovering that the property resides in a landmark district.

Cultivating strategic relationships with community leaders, action-oriented volunteers, and outside specialists was vital. Early on, we initiated a relationship with NeighborSpace, an urban land trust that provides property protection to open space across the city. It took nearly six years to secure land protection in perpetuity as a self-determined community asset. We formed a charitable group as an informal means to represent our goals.

Along the journey, an unexpected encounter from a man on a bike was pivotal. It launched an ongoing artistic relationship between the sculpture garden and independent musicians, a contemporary art museum, and jazz festival organizers.

Activations with Art, Music, and Nature

“I had always been drawn to that place because of the sculptures there. I could see that a deep and visionary spirit had committed to transforming that space,” recalls multi-instrumentalist and Elastic Arts director Adam Zanolini. “So, when I needed to find an outdoor home for the kind of creative music we do, it resonated with me.”

As the pandemic took hold, the sculpture garden was renewed with art appreciation, music, and social gathering. People were starved for connection. The renowned Hyde Park Jazz Festival organized a pop-up “Postcard Series” to bring 30 curated jazz musicians to artist-selected communities across Chicago. Zanolini performed as a duo with Xristian Espinoza. Artmaking demonstrations enhanced the event. “Another reason why the garden is the perfect place for music is because it’s a reawakening of nature in the middle of this huge city where most of nature has been hidden and paved over,” Zanolini adds.

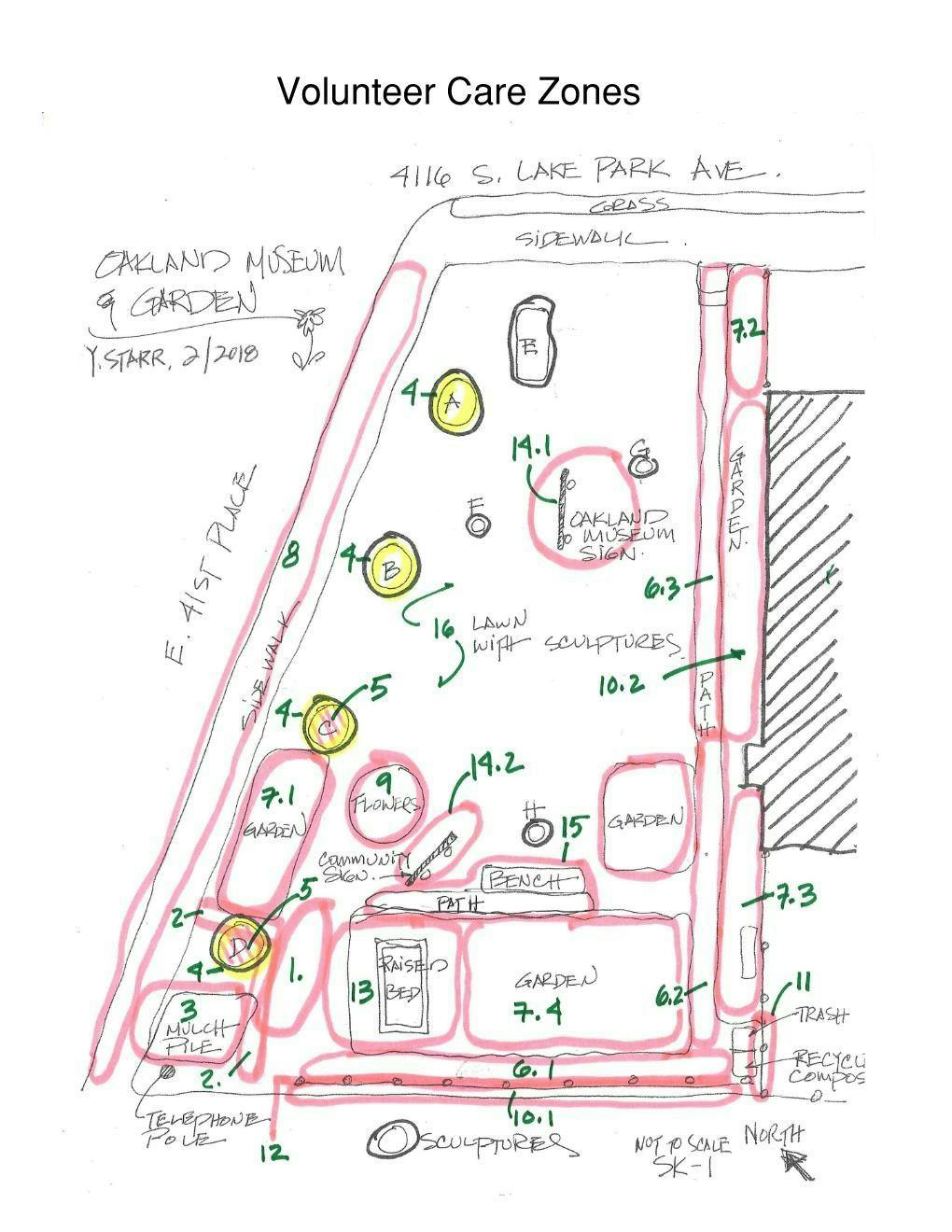

The activations and social gathering experiences drove home our desire for a connection to the outdoors, where nature is intrinsically correlated to healing and positive wellbeing. During the pandemic, we wondered how we could harness the separate but together experience of the art and music events and build enthusiasm to care for the outdoor museum. Garden leaders sketched up a plan with designated “care zones” to allow for a sense of autonomy with a purposeful outcome.

Pride of place and collective momentum ensued while neighbors tended to the land safely and separately. If there was a silver lining from forced isolation, it’s that we discovered a cohesion in community, and open access to the museum garden resonated with residents. Having versatile schedules allowed participants to contribute when they might need to replenish mind and spirit. The activity was remarkably uplifting and continues as a viable and galvanizing approach.

“I’ve gotten to know neighbor volunteers a little better, and they all have a superpower that they can lend to the effort,” says garden leader Robert Kempa. For group participation, we’ve initiated ad hoc Saturday morning care with local high school Kenwood Academy and students from Columbia College’s Interior Architecture program. These cross-generational collaborations cultivate enthusiastic young minds and promote future stewardship.

Adaptability and Making Things

Stepping into a natural setting with no barriers between living creatures—human, plant, animal, and insect—conditions are continuously evolving. Therefore, adaptability is critical in working with underutilized open space in a semi-wild outdoor environment.

For example, we had no funds and little time to renovate a large swath of topography when it came to creating a hardscape performance area. We utilized our design skills and asked several musicians who’ve adopted the space for practice to weigh in on location and size. Landscape design consultant Barbara Siegel Ryan calmed our fears about existing vegetation and guided us to work towards a low-maintenance public space. Collaboratively, we came up with an ample performance area for our cultural events.

To that end, working alongside several outside specialists and committed volunteers with fabricating expertise, we created a hand-carved signage marquee sanctioned by the artist’s family, replacing a deteriorating oversized marker. Chicago-based sculptor and muralist Bernard Williams gave us insight on finishing properties to withstand “lake effect” wind conditions and enhance color vibrancy. Further, with a pilot conservation grant, we began working with L.Liparini Studio & Third Coast Conservation to stabilize several sculptures and plan for future restoration work.

Keeping The Long View

As a designer, I am thrilled to participate in an ongoing legacy project that represents community endurance and stewardship for future generations. Early on, I imagined how tragic it would be for this exuberant artist’s legacy to be remembered on a ubiquitous bronze plaque in front of a bland three-flat apartment. It would never show the spirit of the man, create the unique sense of place he envisioned, or reflect the people he inspired. As musician Zanolini explains, “It’s really a beautiful historical story of a neighborhood being reimagined through art. That’s exactly the kind of transformation we hope to bring to people through the sounds we make—that we can bring people together across differences.”

For me, the focus of the cultural preservation project has been leveraging design and advocacy to holistically invigorate the founder’s legacy of engagement, art appreciation, belonging, and knowledge of the individuals making an imprint on the community. Preserving is considered with a careful legacy and social conscience lens respecting the historical weight around the Chicago Oakland area. Families and businesses are drawn to neighborhoods with cultural heritage, educational, and main street investment initiatives improving quality of life.

As the future unfolds, the Oakland Museum & Garden may be a wonderful example of resiliency and sustained grassroots community cohesion. The sculpture garden is a platform to explore, learn, and engage in the spirit of the founding artist. Milton Mizenburg III, the late artist’s son, says his father “wanted to bring together the community, and apparently it worked.”

About the Author

Yetta Starr

Principal, Starr Design Associates, Inc.

Yetta Starr, IIDA, is the founding principal of Starr Design Associates, Inc., a practice specializing in commercial interiors. She is also executive director of the Oakland Cultural Alliance.

Starr has a passion for engaging with community-based initiatives supporting cultural identity and economic development. She is a contributing writer to print and online publications, reporting on industry trends and impact of design on the human experience. For information about design or community projects: [email protected].