Special Report: Coming of Age

By Katie Sosnowchik

Many diverse professions, such as nursing, law and landscape architecture, have identified concrete bodies of knowledge for each of their respective professions. Recently, the interior design profession has joined their ranks when The Interior Design Profession's Body of Knowledge, 2005 Edition was released to the interior design community this past March. This new edition is an updated version of an original study published in 2001, and was developed by Caren S. Martin, Ph.D., CID, ASID, IIDA, and Denise Guerin, Ph.D., FIDEC, ASID, IIDA, of the University of Minnesota in St. Paul, MN. While the Association of Registered Interior Designers of Ontario (ARIDO) funded the original study, the new 2005 edition signals a joint (and some believe groundbreaking) effort by six professional interior design organizations: the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID), the Council for Interior Design Accreditation (formerly FIDER), Interior Designers of Canada (IDC), the Interior Design Educators Council (IDEC), the International Interior Design Association (IIDA) and the National Council for Interior Design Qualification (NCIDQ). The overarching goal of the 2005 Edition: to continue to define and document the abstract knowledge needed by practitioners to perform the profession's work—and to initiate and sustain a dialogue among educators and interior designers to document changes over time. This edition of the professional practice paper represents a "snapshot" of where the interior design profession's body of knowledge is today.

A body of knowledge report is essential for any profession, especially for one that originated in the early 1900s, notes Martin and Guerin, who said they undertook the project for the value that lies in the discovery and in the research involved. "It is a coming of age activity that [the profession] needed to engage in," Martin describes.

Equally important, the authors note, is that the profession understands that this body of knowledge is not fixed—that it's constantly in a state of flux. By its very nature, knowledge is not static, for it is intrinsically ever-changing. Thus, identifying a profession's concrete body of knowledge is a necessarily complicated and complex pursuit. It is a process that attempts to identify not only that which informs the profession, but also what its practitioners do. The process also attempts to assign value to the services a profession's practitioners provide—services that are inherently linked to the knowledge they possess.

"When we say we 'own' a particular area, what that means is that this is an area of specialization that we are prepared for through our education, experience, examination and regulation," Guerin comments.

Debating a Definition

The idea for The Interior Design Profession's Body of Knowledge, 2005 Edition was first conceived in May 2003, when 25 interior design practitioners, educators and industry representatives from the United States and Canada gathered to debate and attempt to define a body of knowledge for the profession. Participants vigorously articulated various positions on how the profession can best define its knowledge base. Several, for example, argued for defining the profession through descriptive terms rather than by prescriptive skill sets. Another predominant discussion topic centered around what interior design knowledge is proprietary (unique to interior design) and what is shared with other allied professions such as architecture? Additionally, some attendees advocated for the need to spend time and energy communicating interior designers' legitimacy to others, rather than attempting to define it among themselves.

Despite the lively debate, the group did reach one consensus: to propose the document created by ARIDO as a "best effort to date" to summarize a body of knowledge for the profession. By looking comprehensively at content knowledge across the spectrum of education and practice, the ARIDO document demonstrated that there was, in fact, unique and specialized knowledge that interior designers possessed that protected the life, health, safety and welfare of the public.

The report approached the body of knowledge from the perspective of four stages of a career cycle: education, experience, examination and regulation. During its preparation, more than 300 industry-related documents were consulted to "discover and record, through credible sources, what constitutes interior designers' work, that their work requires a specialized knowledge, and that application of that knowledge contributes to the life, health, safety and welfare of the public." Key words from the credible sources documents were compiled into a matrix, which in turn categorized the key words into major knowledge areas in order to illustrate their respective benefits.

All Knowledge is Not Created Equal

While this initial report was an immensely significant first step, it was apparent after the 2003 meeting that additional research was needed. Thus, the six interior design professional organizations joined forces to fund an update of the initial report, charging Guerin and Martin with the task of weighting each of the knowledge areas to determine their levels of importance to the practice of interior design.

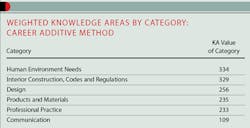

"The first study didn't really differentiate between the knowledge areas in terms of what is more relied upon, more central or key to interior design knowledge," describes Martin. The 2005 edition was designed to clarify that. Most significantly, 96 knowledge areas classified according to six major categories were weighted for importance to practice using the Career Additive Method, which used the documents' internal weighting system multiplied by the number of times the keyword appeared in all documents (see table for weighting results). This method reflected the cumulative learning process of the career cycle. A panel of experts was then used to validate the method, findings and weighting process.

This panel, says Guerin and Martin, was invaluable to the process.

"Any time research is done, it is often done in isolation," comments Guerin. "You follow certain standards and processes and methods and it all seems perfectly logical to you. But before you put it out there for the public to react to, it's most effective if you get input from those who are interested in it."

From the beginning, the authors note, the panel understood that they couldn't change the findings. "What we were after were their eyes on the process that we used," they describe. One way the panel was especially helpful was by categorizing specific knowledge areas.

For example, the knowledge area identified as "problem review and evaluation during alteration and construction" was originally classified under "Human Environment Needs," in large part because problem review addresses the issues of client needs and wants. However, the panel explored how this issue occurred in most of the literature and discovered that it really talked about the process of problem review. Thus, this knowledge area ended up being moved into "Professional Practice." "The value did not change—its location changed," explains Martin.

As for the results, noted Guerin, "I think we were pleasantly surprised. Intrinsically, many designers feel that human environment issues are their real expertise—that we really know how to design for people," she says. "There's now overwhelming evidence for that.

"Secondly," Guerin adds, "one of the most important things that we understand, yet not everyone in the public understands, is that we really know codes and regulations and standards. For those two to come out on top, was quite wonderful in our way of thinking."

Currently, the six associations involved are evaluating the implications of the study and how it can best be utilized. Many professionals, including the authors, look forward to the dialogue it is sure to generate, and how that dialogue might impact the profession in the future.

"It's scary to put down in black and white the body of knowledge of the interior design profession because it takes some of the richness out of the profession in some people's minds," explains Martin. "There's some concern that if you can write this stuff down, then it doesn't account for creativity, for how interior designers think. People have to remember that this report talks about knowledge. It does not talk about skills or paths, it simply talks about what you can keep in your head."

"Whenever you take abstract knowledge for any profession and identify it, define it and document it, you are taking some of the richness out because of the profession's interactive nature," Guerin adds. "So when we draw the Body of Knowledge down into this two-dimensional list, much of the complexity, the collaborative issues between different parts of the knowledge areas, the interdisciplinary aspects—these all seem to be sort of lost. We need to talk about a body of knowledge in a much larger scale—something that shows the strength of the complexity that is based on individual knowledge areas."

"Our greater interest all along has been that this information be more widely available," comments Kayem Dunn, executive director of the Council for Interior Design Accreditation, "and that it generates conversation that helps people think about what updating needs to be done—what different view of the profession might need to be taken to move us forward. How are things going to change? How are they changing? How will they change? That was part of our motivation to be involved and to maintain relevance in what we do."

A copy of the The Interior Design Profession's Body of Knowledge, 2005 Edition can be downloaded on the jointly sponsored career Web site at www.careersininteriordesign.com and via links from the Web sites of the supporting consortium of design organizations.

Katie Sosnowchik is the former editor of Interiors & Sources and is currently working as a freelance writer and communications consultant. She and Penny Bonda are co-authors of Sustainable Commercial Interiors, to be published later this year by John Wiley & Sons.