Although Miami’s design community and international fashion scene are clearly thriving, the city’s architectural community does not seem enormous upon first glance. A deeper look reveals a complex network of designers fractured only by each individual’s disciplinary title. The interviews that Arquitectonica has conducted in this issue of Interiors & Sources function more like field work than boosterism, serving to broaden the identity of this group of spatial practitioners to include developers, urban planners, educators, landscape architects, store owners, fashion designers and retail moguls alongside architects. Locals and visitors alike practicing in these fields think and work in three dimensions and make valuable contributions to Miami’s built environment.

Miami’s seasonal nature makes it conducive to a range of temporary events like fashion shows, art shows, concerts and festivals, events that Miami’s designers use as opportunities to showcase their talents to the world. More consistent operations like retail and hospitality services constantly update their spatial identities, tasking designers with creating memorable experiences that stir the emotions of visitors returning year after year, always with the hope of seeing something new.

The relationship between fashion and architecture that Arquitectonica teases out in this issue involve different ideas of time from each designer interviewed. The most basic connection between fashion and architecture has fashion assumed to be an ongoing series of short-term pursuits that are constantly changing and evolving, while architecture is a long-term pursuit that reaches deep into history and aims to create structures that will stand the test of time.

Arquitectonia’s Miami case study is full of exciting counterexamples to this norm. Miami, with its accommodating climate, pleasure-seeking permanent residents and transient vacation population, sits at the intersections of various geographical regions and routes of commerce, encouraging a transformative architecture that keeps up with styles and trends as much as fashion. Branding strategies applied at a large scale to hotels and condominiums make use of techniques generated in the fashion industry, and are successful with visitors and residents alike.

This article is part of our special section written by guest editors from Arquitectonica.

For More Content from Arquitectonica:

- Editor's Letter

- Intersections

- Lightness: Shohei Shigematsu

- Continuity: Mohsen Mostafavi

- Patina: Raymond Jungles

- Color Blocking: Edwidge Danticat

- Pastiche: Jessica Goldman

- Urbanism: Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk

- Hi-Lo-Tech: Raymond Fort

- Trends: Coworking Spaces

- Flexibility: Olivia Wolfe

- Classic Retail: Stanley Whitman

Miami’s architecture can be short-term just as easily as fashion design can be long-term. The city embraced the fashionable architecture of Morris Lapidus in the 1950s and 1960s; it has been receptive to the boundary-crossing product design, fashion design, interior design and landscape architecture of Arquitectonica since the 1980s; and it has finally grabbed the full attention of members of the contemporary international design scene searching for a city that encourages bold expression.

OMA, always one of the first architectural offices to pick up the scent of an emerging market, is represented here by Shohei Shigematsu, the director of OMA’s New York City office since 2006. Shigematsu joined OMA in 1998, only 10 years before becoming a full partner, and is now responsible for most of OMA’s North American activity. Since taking over, Shigematsu has given the OMA NYC office a personality both in line with and distinct from OMA’s main Rotterdam office, adding a lightness of touch previously missing from OMA’s relatively heavy and bold work. Shigematsu’s appreciation for the speed of the fashion industry is apparent in the office’s use of countless iterations of physical models and samples to test designs at full scale. This reciprocity has led to recent projects with fashion houses and retail stores that have allowed Shigematsu and the OMA NYC office to put their research to practice.

Raymond Fort, son of two of the founding partners of Arquitectonica, is the only other architect and the only local architect featured in this issue. One generation younger than Shigematsu, Fort is just making the switch from academics to practice, having recently graduated from Cornell’s School of Architecture, Art and Planning (2011) and Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (2012). Fort’s childhood was spent in Miami, giving him a longer perspective on the transformations of the city than Shigematsu and many of the other designers recently involved in Miami’s architecture boom.

At Arquitectonica, Fort is already establishing his own architectural identity (as in the University of Miami School of Architecture building), but as a young architect still learning the trade, his clothes and habits allow more room for expression. For Fort, animations that convey change over time have replaced renderings and a MakerBot 3-D printer has become as comfortable a sketching tool as a pencil and paper. As a connoisseur of the Miami lifestyle, Fort is involved in both short-term and long-term design around the city.

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk is another longtime Miami resident with a complex perspective on the city. Three years after founding Arquitectonica in 1977 with Andres Duany, Bernardo Fort-Brescia, Laurinda Spear and Hervin Romney, Plater-Zyberk formed the urban planning office DPZ with Duany. Rather than lighting a spark of innovation in Miami, as Arquitectonica aimed to do with its work, Plater-Zyberk and Duany were interested in creating and promoting urban continuity and connectedness, particularly through the ideals of the New Urbanism school that they formed; they felt that it was easier to effect fundamental changes to the way a community works without making radical aesthetic adjustments. Plater-Zyberk explains in her interview that an almost-two-decade long deanship at the University of Miami has given her a platform to identify problems for the city to tackle and to develop UM’s campus as if it were a city in itself.

Like Plater-Zyberk, Mohsen Mostafavi is the dean of a prestigious design school, Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Mostafavi gives us the historical perspective of fashion’s relationship to architecture, reaching back to places and times that existed centuries before Miami was even an incorporated city. He also points out that the mutual growth between the two that seems to be developing spontaneously in Miami is not new at all, but is instead just given a renewed emphasis today. From Boston, Mostafavi is able to locate Miami in its place among the periods of history in which boundaries between design scales were blurred. Long immersed in student life, Mostafavi sees the fashions that pass through the architectural work of students as equally valid windows into their personalities as their clothing choices.

Plater-Zyberk’s and Mostafavi’s roles as leaders of admired schools pull them into political realms that they eagerly dive even further into with urbanism projects and participation on juries. Jessica Goldman, CEO of Goldman Properties, confronts similarly charged public issues through her dual roles as real estate developer and museum curator. Goldman has been involved in the creation of new neighborhoods her entire life, from her family’s move into SoHo in the 1980s to their move to Miami Beach’s South Beach, where Goldman managed properties after working as a fashion director. Goldman focuses most of her attention these days on Wynwood, which she and her family targeted as a potential cultural district when it was still filled with auto shops and storage warehouses. Embracing the neighborhood’s rugged roots, aside from running her family’s company, Goldman closely manages Wynwood Walls, a street art museum and event space that has quickly become one of Miami’s main attractions.PageBreak

Arquitectonica has uncovered many overlooked perspectives regarding the relationship between fashion and architecture, and some of the most counterintuitive and insightful come from a landscape architect, Raymond Jungles, and an author, Edwidge Danticat, who see through assumptions and are able to recognize fashion’s expansion into the physical and cultural landscapes. Jungles’ landscape architecture practice, based in Miami since the early 1980s, designs urban landscapes, parks, private gardens, restaurants and hotel grounds that are harmonious with their social, environmental and programmatic contexts. Jungles proposes that regardless of whether landscape architecture is understood as clothing, framing or even interrupting architecture, it changes and can be changed at a different pace than both buildings and clothing.

From an early age, Danticat has used words to create her spaces and concepts of time. A result of her unique upbringing in Haiti and New York City, Danticat’s appreciation for color extends to both the wearable and built environments. The symbolism and rhythms that color can add to lifestyles and buildings are expressed in Danticat’s writing. Her evocative settings and analyses of Haitian life reveal that she cannot resist the influence of either architecture or fashion, and her written descriptions are as valuable to a cultural understanding of urban fashions as designed projects.

Like Jungles and Danticat, Miami natives Olivia Wolfe and Stanley Whitman both found success at an early age, more directly in fashion and within architecture. Wolfe, co-founder of the clothing store and hangout American Two Shot with Stephanie Krasnoff, has been in the retail business for only a few short years, but an appreciation for spatial flexibility and personal connections has allowed American Two Step to flourish in SoHo. Wolfe represents the insertion of Miami’s laidback fashion culture in the center of New York City’s shopping district, a distinct shift from the typical infusion of New York City fashion in Miami.

Whitman’s Bal Harbour Shops were a similarly instant hit, on a much larger scale and across many decades. Whitman’s devotion to quality and consistency has led to his shopping center becoming the prototype of high-end retail since its opening in 1965. His deep ties to Miami Beach—Whitman’s father owned the first hotel and second telephone on Miami Beach in the 1920s and even developed Española Way—reveal perhaps the deepest personal influence on Miami in the magazine. He reminds us that even though the relationship between fashion and architecture may be a recurring theme in Miami’s history, the city itself is barely a century old. As Miami’s newest visitors learn quickly, the city’s relative youth is a valuable part of its intrigue.

Tucked within these nine interviews are a number of examples of short-term architecture and long-term fashion. Goldman discusses evolving walls, Shigematsu and Wolfe talk adaptive interiors, Danticat explains how color can be an expression of a building’s mood, Mostafavi observes the potential of scale mockups of building parts, and Fort points to his personal style as a preface to his built architecture. Meanwhile, Jungles clothes Miami’s built environment in contextual verdure that is meant to improve with age, Plater-Zyberk explores urban planning models for the city using her own school and campus, and Whitman solidifies the fashionable shopping ideal in the architecture of his Bal Harbour Shops.

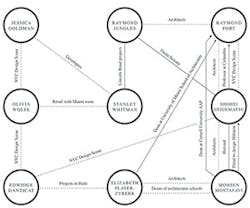

Arquitectonica has been focusing its lens on Miami for almost four decades, and now, at the start of the city’s most recent construction boom, the office has used its considerable experience and insights to offer a roadmap to understanding Miami’s architectural community. Like their own buildings and drawings, this roadmap is full of unanticipated color and expression. As the geographic table of contents and the social connections diagram below attest to, Miami is a city of intersecting paths and motivations. And as the interviews reveal, these intersections shape the built environment of Miami, once the playground of America and now the home of pioneering fashion and architecture.