Transform it, and They Will Come

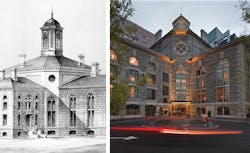

New four-star hotels aren't necessarily big news. But when one opens in a historical space, say, a 19th century jail, it naturally generates a buzz. In the case of the recently opened Liberty Hotel—which has its public spaces and a score of guestrooms housed in Boston's former Charles Street Jail—there's good reason for the stir.

The hotel complex includes a new 16-story ironspot-brick and glass tower containing about 280 rooms, so melding the old and new was a design goal. Because the jail would automatically generate a clientele of the curious, the old jail offered a natural location for the lobby, meeting rooms, ballroom, and three "dining venues" that draw their names from the building's history: restaurants Clink and Scampo ("escape" in Italian), and the Alibi bar.

The jail was a cutting-edge facility when it opened in 1851. Designed by Gridley James Fox Bryant, the cruciform building, with its soaring octagonal rotunda, was a leading example of the "Boston Granite School" of architecture. Tiers of windowless cells ran down the center of each wing. Fresh air and natural light could reach prisoners through three-story, triple-hung arched windows set in the exterior walls, separated from the cells by a board void.

"We wanted to make a clear difference between the historic old and the new design work, set in the framework of the old," says the Liberty Hotel project's principal-in-charge, Gary Johnson, AIA, of Cambridge Seven Associates in Cambridge, MA. "Everything we've done with the hotel, we've done in a contemporized way. Hotel guests appreciate clean lines, and that's a great contrast with the old building. With everything—inserting casework, moldings—we wanted a clean break between the old and the new. We wanted the new tower to be a contemporary building of its time, as the jail was in 1851."

Though the jail was declared unfit for habitation in 1973, it was a home away from home for mooks, mugs and mobsters awaiting trial, until 1990. Among the "guests" were the Boston Strangler and conman Frank Abagnale, whose exploits inspired the movie "Catch Me If You Can."

Johnson first saw the interior of the old jail about a decade after the last prisoners had flown the coop. He recalls the inside of the old building as "decrepit, and a little creepy," with thick, peeling layers of lead-based paint. It contained some obsolete medical equipment stashed there by its owner and neighbor, Massachusetts General Hospital, a clutter of abandoned jail mattresses, and "assorted vermin and rodents."

The adaptive reuse of the building offered the opportunity of a lifetime, though one that came with a host of challenges, such as maintaining the structure's unique elements while making the spaces comfortable and

functional. The goal was to embrace the building's history, keeping elements of the jail visible while changing the aspect from forbidding to inviting. "We had to transform the space from a 19th century jail to a 21st century hotel—from a sorrowful building to a joyful one," explains Johnson.

Project manager Winston Kong, a senior associate of Alexandra Champalimaud and Associates of New York, concurs. Citing the building's neighbors and its original purpose, Kong states, "People try to avoid hospitals and jails, so how to treat those elements was a driving force."

An unexpected discovery in the rotunda led to a design inspiration. When Johnson first saw the rotunda, the ceiling was 40 to 50 feet high, which he assumed was the original height. "I didn't think much of it," he says. Much later in the project he found out there was an additional 40 to 50 feet of space above the existing ceiling. "I climbed up there [and] it was a little frightening. [But] when I saw what was up there, the project crystallized," adds Johnson. His discovery: four oculus windows, and fir and hemlock queenspost trusses supporting the roof and original decking. "With the rotunda's exposed brick and the trusses, I began to see it could be this wonderful space, almost 90-feet tall. The lobby could be a city living room." With the warm wood tones lighted properly, "it could be a magical space ... a very contemporary interior within a 19th century volume."

Adding a human scale to the expansive hotel lobby was important, says Kong. Four murals of the Tree of Life, inspired by Boston's Liberty Tree, extend up through the rotunda, drawing the eye upward, and uniting the ground floor entry area with the upper lobby. Champalimaud-designed wrought-iron chandeliers mimic the shape of the oculus windows. Principal designer Alexandra Champalimaud went to the site the day the chandeliers were hung, "to gauge the height and bring the rotunda down a bit, so you don't feel you're in a cavernous space," notes Kong.

There's an almost theatrical impact to entering the lobby on an escalator from the street-level entrance, "ascending into a great expansive space flooded with light" is intended to be "an uplifting experience," according to Kong. A ceramic mural by Coral Bourgeois separates the escalators. The tiles depict jail themes, including caricatures, stick figures, fingerprints, and even a depiction of a Champalimaud family friend.

To boost the hotel's appeal as a gathering space, comfortable seating was installed throughout the lobby. The Alibi bar, located in the jail's former drunk tank, and decorated with celebrity mug shots and alibis of the rich and famous, was tucked beneath a catwalk "to make the space more intimate," adds Kong.

Because the Charles Street Jail was on the National Registry of Historic Landmarks, the team on the $150 million project worked with agencies including the National Parks Service, the Boston Landmarks Commission, the Massachusetts Historical Commission, and Beacon Hill and West End neighborhood groups. Elements of "jailness," a term coined by the Parks Service during the project, include preserving some original cells, the exterior windows, exposed brick walls, iron catwalks, and even some barred windows. The wood floors in the Alibi and Clink have granite inlays outlining the perimeter of former cells.

The Liberty's design emphasizes granite, exposed brick, and other materials often seen throughout the hotel's Beacon Hill neighborhood. "We didn't want to introduce other materials that would compete," says Kong. Soft goods in a rich color palette of historical 19th century maroon, gray, and purple hues, were designed for their unique setting. The iron catwalks inspired the guestrooms' drapery fabric; the ballroom's carpet pattern is drawn from windows seen throughout Beacon Hill; and the bed skirts and throws are intended to look like mover's blankets, "to make it feel like you're using whatever you've got," as some of the prisoners might have done, suggests Kong.

Johnson says the design aims to honor history with contemporary vibrancy. "Good design doesn't have to be about a particular period or look—it's about good design. The jail was a handsome piece of architecture in its own right, and the new should be equally nice. They should be handsome together and compatible."

Johnson anticipates an increase in creative and adaptive reuse projects, although it's a more costly approach than starting from scratch. "People are beginning to value historic buildings," he says. "In Boston in particular, due to the historic fabric of the city, there is interest in maintaining existing building stock, bringing these buildings to current standards." With the current interest in the greening of America, the rest of the country is likely to follow suit.

Elzy Kolb is a White Plains, New York-based freelancer writer, editor, and copy editor. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, Westchester magazine, TheStreet.com, and many industry publications.

IMAGES:

back to top

SOURCES:

back to top

|

LOBBY CARPET TREE WALL PANELS CHANDELIERS SEATING UPHOLSTERY FABRICS WOOD TABLES LEATHER TOP TABLES TIERED METAL TABLE FLOOR LAMPS TABLE LAMPS TILES (AT ESCALATOR) CLINK BAR DINING CHAIR DINING CHAIR FABRIC |

DINING TABLE (TOP) DINING TABLE (BASE) BANQUETTE CHAIRS BANQUETTE CHAIRS (UPHOLSTERY) PENDANT WALLCOVERING ARTWORK/ART CONSULTANT SUITE CARPET UPHOLSTERED SEATING UPHOLSTERY FABRICS Nobilis CASEGOODS TABLE LAMPS PENDANT (AT DINING TABLE) |

WINDOW TREATMENT Rogers & Goffigon Ltd. BATHROOM WALL SCONCE BATHROOM TILE GUESTROOM CARPET CASEGOODS UPHOLSTERED SEATING UPHOLSTERY FABRICS Moore & Giles TABLE LAMP/DESK LAMP/FLOOR LAMP WINDOW TREATMENT WINDOW TREATMENT FABRIC (OVERDRAPE) WINDOW TREATMENT FABRIC (SHEER) BATHROOM WALL SCONCE BATHROOM TILE |

PRESIDENTIAL SUITE CASEGOODS UPHOLSTERED SEATING UPHOLSTERY FABRICS Pierre Frey Brunschwig & Fils Decorators’ Walk PENDANT (DINING TABLE) DECORATIVE LIGHTING TABLE LAMP/DESK LAMP/FLOOR LAMP Selezioni WALLCOVERING WINDOW TREATMENT POWDER ROOM WALL SCONCE |

CONTACT:

back to top

|

CLIENT Liberty Hotel PROJECT TEAM ARCHITECT Gary Johnson, principal-in-charge |

HISTORIC PRESERVATION ARCHITECT Pamela Whitney Hawkes, principal LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS Michael Van Valkenburgh |

INTERIOR DESIGNER Alexandra Champalimaud, president and principal ID |