New Ruralism Meets New Urbanism

In 2008, the world passed a watershed point – more people now live in cities than not. As architects, how we make these cities, and how these cities relate to the rest of the world, will be critical. As history demonstrates, cities have the potential of being very efficient organizations. A city can house many with a limited use of land, and stimulate social, educational, and political discourse. Today, however, cities need to be made more livable than ever.

Concepts for Smart Growth and New Urbanism have been shared and debated for some time among architecture and urban design professionals. A relatively new movement, called New Ruralism, which is led by Sibella Kraus of Sustainable Agriculture Education and the University of California at Berkeley’s Agriculture at the Metropolitan Edge program, has been gaining recent momentum. It’s based on improving city design by bringing country living back into the city. There’s been a big push to encourage urban planners and architects to incorporate farmland into their design plans.

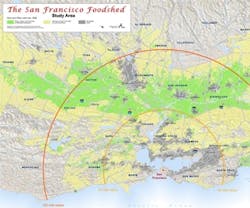

New Ruralism envisions architects, planners, and developers working together with farmers and policymakers, paying close attention to foodsheds (local food production and distribution systems that are intended to produce healthy, abundant food without the use of fossil fuels or the exchange of money, and to foster the development of community). Important links are forged between urban dwellers and farmers. As more urbanites come to value this connection, reverence and concern for the future of the land heightens.

Over the past 10 years, architectural firms, including San Francisco-based BCV Architects, have designed a number of significant buildings that contribute to the idea of New Ruralism. BCV has designed market halls in California, including the San Francisco Ferry Building, which brings local producers from the Bay Area foodshed into an urban environment to sell their products.

At the heart of the Ferry Building is a 3-story, sky-lit hall (the Nave). It runs the entire 660-foot length of the building, and daylight fills the Nave from the steel-trussed glass ceiling. The design of the building is key to the purpose it serves.

The ground floor of the Ferry Building is devoted to a 65,000-square-foot public food market. The second and third floors of the building house 175,000 square feet of office space and the ceremonial hearing room of the San Francisco Port Commission.

The concepts of New Ruralism are also central to strategies for the design of a new neighborhood for San Francisco: Treasure Island. The 400-acre island – slated to undergo a major transformation that will result in more than 300 acres of open space – is destined to become one of the foremost transit-oriented, sustainable urban enclaves in the United States.

The Master Plan for Treasure Island, a collaboration between BCV, Conger Moss Guillard, Hornberger + Worstell, Perkins + Will, and Skidmore Owings and Merrill (SOM), includes housing for more than 6,000 residents within a 10- to 15-minute walk to a new ferry terminal that connects to San Francisco. More than 60 percent of the island is planned to be public open space, including parks, fields, trails, and an urban organic farm. Plans include the reuse of one of the airplane hangars as a market hall and artisan food production facility.

In 2008, BCV helped rally 20-plus Bay Area design firms to assist with the planning, design, and fabrications for Slow Food Nation ’08. Relationships were forged between architects, landscape architects, urban designers, food producers, farmers, chefs, policymakers, and educators in the sustainable agriculture movement.

For a generation of architects, planners, and urban designers, building mixed-use, transit-oriented communities has been central to the principles of New Urbanism. New Ruralism reminds us that cities do not exist in isolation and can be made richer by celebrating the connection to their food sheds, providing a layer of potential programming, diversity, and connections. This layer is full of opportunities for education and enjoyment of sustainable principles and community building, which lead to healthier cities and individuals. Bringing agricultural pursuits closer to the city builds a region’s identity and the consumption of the products of that region supports the local economy.