Performance-Based Fire Modeling: Unlocking Design Freedom While Meeting Egress and Life Safety Codes

Why This Matters to Architects and Designers

- Performance-based fire modeling allows for greater design flexibility by demonstrating safety through simulations rather than strict code adherence.

- Tools like CFD and egress modeling help evaluate ASET and RSET, ensuring safe evacuation even in complex or constrained layouts.

- Transparent communication and early involvement of experienced fire protection engineers and AHJs are crucial for successful implementation of performance-based strategies.

Imagine designing a modern event space inside a beautiful historic building, only to learn that life safety code requirements demand an additional exit stairway that would completely disrupt the open layout. This is a familiar problem for architects and interior designers working on adaptive reuse or renovation projects.

Whether transforming a post office into a food hall or converting an office floor into a rooftop lounge, code-mandated exit widths, stair counts, and travel distance limits can force painful compromises. In many cases, they result in reworked layouts or expensive retrofits that clash with the original design vision. There is another path, however. A performance-based fire and egress modeling approach offers greater flexibility and a way to balance design intent with life safety compliance.

The Code Challenge

Building and life safety codes, such as the International Building Code (IBC) and NFPA 101, calculate occupant loads (The total number of persons that might occupy a building or portion thereof at any one time, as per NFPA 101) using occupant load factors (OLFs). These factors represent the number of square feet allocated per person, based on a space’s intended function.

Developed from research on human behavior and historical building data, OLFs estimate the typical occupant density for different use types. The denser the assumed use, the lower the OLF and the higher the calculated occupant load. This, in turn, drives critical design decisions for exit widths, stair sizes, and the number and spacing of exits.

This code-based logic becomes a barrier in many uses. For example, converting a 30,000-square-foot former warehouse into an event venue might increase the calculated occupant load from approximately 100 warehouse staff to over 4,200 guests. This spike, driven by a shift from low-density storage use to high-density assembly occupancy, can require multiple additional exits, significantly wider stairs, and major upgrades to life safety systems, demands that may not be feasible within the original building layout.

In another example, a 20,000-square-foot open-plan office is converted into an ambulatory care clinic. Although the occupant load remains the same, the new use group (Ambulatory Care as per NFPA 101) comes with stricter egress requirements.

While the original office layout permitted travel distances up to 300 feet in a sprinklered building, ambulatory care occupancy limits travel distance to 200 feet due to potential patient mobility issues. With enclosed exam rooms and long internal corridors, the new clinic layout may necessitate pushing some spaces beyond that distance, requiring an additional exit or reconfiguration of egress paths. In both scenarios, prescriptive code threatens to conflict with the architectural intent.

When prescriptive code threatens to conflict with architectural intent, performance-based design offers an alternative that meets life safety requirements while preserving design integrity.

From Prescriptive Code to Performance-Based Design

Prescriptive codes provide detailed tables and formulas that apply broadly across building types. These include fixed rules on maximum travel distances, minimum stair widths, and the required number of exits. While these standards ensure a baseline of safety, they do not account for the unique opportunities or constraints of a specific project.

Performance-based design offers an alternative. Rather than following a checklist, the design team works with a qualified fire protection engineer to prove that occupants can evacuate safely under fire conditions, even if the layout doesn't meet all prescriptive requirements. The key is to demonstrate that the building meets or exceeds the level of life safety intended by the code.

This approach generally evaluates and compares two key metrics:

- ASET (Available Safe Egress Time): How long the environment remains survivable during a fire before smoke, heat, or toxic gases make egress paths untenable.

- RSET (Required Safe Egress Time): How long does it take for all occupants to detect the fire, react, and evacuate to safety.

If RSET is less than ASET, with a suitable margin of safety, the design meets life safety goals even without following the prescriptive code checklist.

What Is Fire Modeling, and How Does It Work? (Garbage In, Garbage Out!)

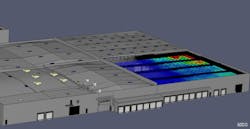

Fire modeling is the primary tool used to support performance-based design. Engineers utilize computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software, such as NIST’s Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS), to simulate the behavior of fire, smoke, heat, and toxic gases within a building over time. The space is divided into thousands of 3D cells, each solving equations for mass, momentum, energy, and chemical species. Egress modeling tools, such as Pathfinder, are then used to simulate how occupants move through the space during an emergency. These models can account for individual behavior, including walking speed, response time, and crowd flow through the exits.

Together, the fire and egress models help determine ASET and RSET with a level of detail far beyond what prescriptive code can provide. If the analysis shows that everyone can evacuate safely based on realistic fire growth, detection, and human behavior, the design can be submitted for approval as a performance-based alternative.

However, this is not a plug-and-play solution. The modeling is only as accurate as its assumptions. Inputs like heat release rate, materials, ventilation, and human behavior must be carefully selected, validated, and checked for sensitivity. A poorly calibrated model could produce misleading results and a false sense of safety.

The next time you’re up against an occupant load challenge or egress constraint that threatens to derail your concept, remember:

The code allows more than one way to demonstrate safety.

Benefits of Performance-Based Fire Modeling

For architects and designers, the advantages of this approach can be substantial.

- Preserve design freedom: Maintain open layouts, historic features, and creative spaces that prescriptive codes might restrict.

- Avoid costly retrofits: Fire modeling can often replace expensive changes, like new stairs or widened corridors, with additional detection or suppression systems.

- Enable adaptive reuse: Older buildings that fall short of current code can often meet safety goals through modeling and targeted system upgrades, if needed.

- Build confidence: AHJs (Authorities Having Jurisdiction), clients, and end users gain assurance through clear, data-supported visuals and documentation that safety standards are being met.

Performance-based design is not for every project. It comes with its own set of challenges:

- Specialized expertise required: Only qualified fire protection engineers should perform this work. Inexperienced inputs can compromise safety and credibility.

- Resource-intensive: Simulations are iterative and must start early to avoid late-stage design changes and delays.

- Approval not guaranteed: AHJ acceptance varies, and some jurisdictions may be less comfortable with non-prescriptive approaches. Early and transparent collaboration is the key.

Embracing a Powerful Tool for Design Freedom

To ensure a successful performance-based strategy, early planning is critical. Bring in a fire protection engineer during the schematic design phase, even before code issues surface. Involve AHJs from the beginning; share the modeling approach, discuss key assumptions, and invite feedback. And above all, work with experienced professionals who can deliver technically sound models and communicate them clearly to stakeholders.

Ultimately, performance-based fire modeling is more than a technical workaround; it’s a creative enabler. It gives architects and designers the ability to prove that their vision is safe, even when the code’s default formulas say otherwise. Whether preserving a landmark, transforming a warehouse, or breathing new life into an old office floor, fire modeling enables architects to move forward confidently, knowing that they’re not only safeguarding their design vision but also protecting the lives of the occupants.

So, the next time you’re up against an occupant load challenge or egress constraint that threatens to derail your concept, remember: The code allows more than one way to demonstrate safety. With the right team, tools, and approach, performance-based modeling can turn a roadblock into a breakthrough.

About the Author

Saleel Anthrathodiyil

Saleel Anthrathodiyil, PE, CFPS is a Fire Protection Engineer at Telgian Engineering & Consulting (TEC). Anthrathodiyil has extensive experience in smoke control design, fire and egress modeling, hazardous materials analysis, and regulatory code consulting. He specializes in performance-based fire engineering, NFPA/IBC code interpretation, and third-party inspections and testing. His experience offers a strong track record of effective collaboration with AHJs, ensuring clear communication, timely approvals, and reduced project risk. Saleel Anthrathodivil can be reached at [email protected].